The Critical Role of Environmental Hygiene in the Prevention and Control of Candida auris

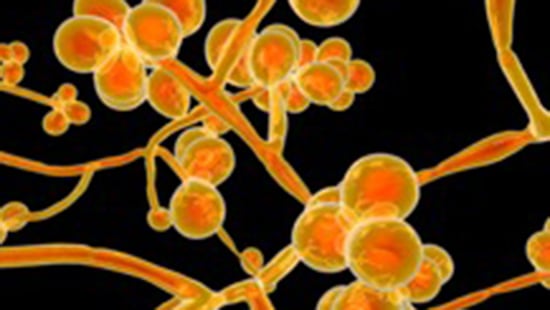

Candida auris is an emerging, multi-drug resistant fungi that is highly transmissible. The name, “auris” is derived from the Latin word for ear, because this was the first body site in which the fungi was identified.1 As with other Candida species, C. auris colonizes the skin, mucous membranes, gastrointestinal tract and the female genital tract. Five to ten percent of susceptible patients develop invasive infections, such as bloodstream infections, with high mortality rates. Infections caused by this organism have been tracked carefully and, until recently, were thought to occur due to exposure to antifungal drugs rather than via person-to-person transmission. However, in July 2021, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a report confirming transmission from patient-to-patient.2

In the wake of this new understanding that C. auris can be transmitted from person-to-person, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) released a statement urging healthcare facilities to adopt aggressive infection prevention and control measures to stop the spread of C. auris in healthcare settings.3 The most important prevention and control measures, as described by the CDC and reinforced by APIC, include:4

- Adherence to hand hygiene – Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are effective against C. auris, and are the preferred method for hand hygiene when hands are not visibly soiled.

- Transmission-based precautions are applied based on the setting, as with other multi-drug resistant organisms.

- Early identification and susceptibility testing, followed by coordinated communication between laboratory and clinical staff and between facilities is critical when C. auris is identified.

- Meticulous cleaning and disinfection of the patient care environment that is confirmed by increased environmental monitoring in patient care areas.

As we have seen with other pathogens of concern such as C. difficile, these guidelines reinforce the critical role that the environment plays in the transmission of C. auris. Studies have determined that this organism can survive on moist and dry surfaces for up to one month.3,5 Even more challenging, there is evidence that it can survive in both wet and dry biofilms, making it harder to eradicate from the environment once it has been introduced.6.

In 2020, the CDC created Core Components for Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection in Hospitals.7 These core components outline an effective environmental hygiene program and are more important than ever when faced with an emerging pathogen such as C. auris. Let’s look at these Core Components and how relate to management of C. auris:

Integrate EVS into the hospital safety culture.

Providing a clean patient environment is a cornerstone of a hospital’s safety culture. To prevent transmission of C. auris, frequent communication and collaboration between departments is critical. When patients are diagnosed or admitted with C. auris, the Environmental Services department must be promptly notified so that C. auris protocols can be activated.

Educate and Train.

When novel pathogens such as C. auris arise, all staff must be educated on the organism, its transmission, transmission-based precautions needed, and specific practices and products that must be incorporated to prevent transmission. Reinforce concepts with ongoing education with new healthcare personnel and as new guidance becomes available.

Select products that are effective against the organisms of concern.

There have been several studies that evaluate the efficacy of disinfectants against C. auris.8 The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains List P, which includes all EPA-registered antimicrobial products with claims against Candida auris, along with their contact times.9 Among the active ingredients that are effective are hydrogen peroxide/peracetic acid, dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DDBSA), hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite. If products on List P are not accessible or are otherwise unsuitable, interim CDC guidance permits the use of an EPA-registered, hospital- grade disinfectant that is effective against C. difficile. Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) are widely used as disinfectants in healthcare. However, data from recently published studies indicates that products whose only active ingredient is QAC are not effective against C. auris.4,10 Regardless of the product selected, it is important to read label claims and follow all manufacturer’s instructions for use, including applying the product for the correct contact time.

No-touch technologies such as vaporized hydrogen peroxide or germicidal UV irradiation are increasingly integrated into terminal cleaning processes.11 While there is limited research about the efficacy of these technologies specifically against C. auris, they may be an adjunct to routine cleaning and disinfection processes. Decontamination with 35% hydrogen peroxide vapor was deployed as part of a range of measures to successfully control a C. auris outbreak in a European hospital.12 In laboratory testing, Candida auris and two other Candida species were significantly less susceptible to killing by UV-C than MRSA.13

Standardize protocols.

The CDC C. auris guidelines recommend meticulous attention to daily and terminal cleaning/disinfection of all patient rooms, all areas where they receive care, and all shared equipment. C. auris has been cultured from many locations in patient rooms, including high touch surfaces and general environmental surfaces such as windowsills. Shared equipment such as glucometers, blood pressure cuffs and nursing carts have also been found to be contaminated with C. auris.4

Monitor Adherence and Provide Feedback.

Disinfectants are only effective when consistently and correctly applied. Objective monitoring and feedback on the thoroughness of cleaning using objective methods such as fluorescent markers are essential to ensure that critical surfaces and equipment have been disinfected. The CDC C. auris guidelines recommend increased environmental hygiene monitoring when there is a patient with known/suspected C. auris in the facility.4 Environmental hygiene monitoring data must be shared with staff and leadership to drive continuous improvement. For more information on evaluating environmental cleaning, review the CDC Toolkit: Options for Evaluating Environmental Cleaning.14

We now understand that Candida auris, a very dangerous emerging pathogen, can be transmitted easily from patient-to-patient, with the healthcare environment as a key vector. Once again, environmental hygiene plays a central role in preventing transmission of this emerging infection. The CDC has published recommendations for infection prevention for Candida auris, including the use of disinfectants that are effective against C. auris and increased environmental hygiene monitoring to ensure cleanliness. These pathogen-specific recommendations dovetail into previously published Core Components of Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection in Hospitals.

References

- Satoh, K., Makimura, K., Hasumi, Y., Nishiyama, Y., Uchida, K., & Yamaguchi, H. (2009). Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiology and Immunology, 41-44.

- Lyman M, F. K. (2021). Notes from the Field: Transmission of Pan-resistant and Echinocandin-resistant Candida auris in healthcare facilities - Texas and the District of Columbia, January-April 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 1022-1023.

- Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. (2021, July 28). APIC Statement: With resistant C. auris spreading, healthcare facilities must adopt aggressive infection prevention and control measures. Retrieved from Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology: https://apic.org/apic-statement-with-resistant-c-auris-spreading-healthcare-facilities-must-adopt-aggressive-infection-prevention-and-control-measures

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, July 19). Infection Prevention and Control for Candida auris. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-infection-control.html

- Piedrahita, C., Cadnum, J., Jencson, A., Saikh, A., Ghannoum, M., & Donskey, C. (2017, July 28). Environmental surfaces in healthcare facilities are a potential source for transmission of Candida auris and other Candida species. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 1107-1109. Retrieved from Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology: https://apic.org/apic-statement-with-resistant-c-auris-spreading-healthcare-facilities-must-adopt-aggressive-infection-prevention-and-control-measures/

- Ahmad, S., & Alfouzan, W. (2021). Candida auris: Epidemiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, antifungal susceptibility, and infection control measures to combat the spread of infections in healthcare facilities. Microorganisms, 807-832.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, October 13). Reduce Risk from Surfaces: Core Components of Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection in Hospitals. Retrieved from Centers for Diease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/environment/surfaces.html

- Ku, T., Walraven, C., & Lee, S. (2018). Candida auris: Disinfectants and Implications for Infection Control. Frontiers in Microbiology, 1-12.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, July 21). List P: Antimicrobial products registered with EPA for claims against Candida auris. Retrieved from EPA: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-p-antimicrobial-products-registered-epa-claims-against-candida-auris

- Cadnum, J., Shaikh, A., Piedrahita, C., & al, e. (2017). Effectiveness of disinfectants against Candida auris and other Candida species. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 1240-1243.

- Weber, D., Kanamori, H., & Rutala, W. (2016). "No Touch' technologies for environmental decontamination. Focus on ultraviolet devices and hydrogen peroxide systems. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 424-31

- Schelenz, S., Hagen, F., Rhodes, J., Abdolrasouli, A., Chowdhary, A., Hall, A., . . . Fisher, M. (2016). First hospital outbreak of the globally emerging Candida auris in a European hospital. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, 1-7.

- Cadhum, J., Shaikh, A., Piedrahita, C., Jencson, A., Larkin, E., Ghannoum, M., & Donskey, C. (2017). Relative resistance of emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris and other Candida species to killing by ultraviolet light. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 94-96.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010, October 15). Healthcare-associated Infections: Options for Evaluating Environmental Cleaning. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/toolkits/evaluating-environmental-cleaning.html